What I Gained from Attending Professor Luo Xiang's Lecture at My University

Recently, I had the privilege of returning to my alma mater, Foshan University, to attend a live lecture by the widely popular Professor Luo Xiang. I felt a swirl of inexplicable emotions but struggled to articulate them. So, I decided to jot down whatever came to mind.

We Are All Legal Illiterates

Having worked in the legal field for over a decade, I often feel helpless, questioning whether my abilities are inadequate or if my university background is insufficient. I frequently experience a sense of incompetence and even insecurity, feeling overwhelmed by the expertise and skills of my peers. Sometimes, I don’t know how to tackle new issues, where to begin with difficult problems, or how to cope with unavoidable situations, leaving me in constant internal turmoil.

Professor Luo’s lecture was held at the Xianxi Campus of Foshan University, where I began my university journey. It was there that I spent the most carefree and joyful years of my life. Perhaps because my university days were too comfortable, I later faced repeated setbacks in society, transitioning from a state of “calm and competence” to one of “rushing and stumbling.” Nevertheless, I’m grateful that I chose Foshan University and the field of law back then. Despite the bumps and hurdles after graduation, I eventually returned to Foshan and resumed my legal career.

A recurring theme in Professor Luo’s lecture was “I am a legal illiterate” and “We are all legal illiterates.” He cited numerous criminal justice cases, most of which involved various branches of law, including administrative law, economic law, natural resources and environmental protection law, and international law. Whenever he discussed cases spanning multiple legal domains, he would humorously draw out his words and mock himself as a “legal illiterate.”

Indeed, the vastness of China’s legal system is undeniable. For instance, he raised questions like: “What species of parrots can you buy without committing a crime?” “When and where does using a slingshot to hunt sparrows become a crime?” “Which medications purchased online from overseas could lead to criminal charges?” “Is exploiting loopholes in connecting flight tickets a crime?” “Does running an unlicensed square dance training class constitute a crime?” and so on.

The truth is, even specialized legal professionals or scholars in these areas might struggle to provide quick answers. Often, their conclusions could be wrong because the complexity of branch laws sometimes involves not only national regulations but also documents from provincial or even county-level authorities, making it nearly impossible to account for every detail. This is especially true in criminal justice, which strictly adheres to the principle of “nulla poena sine lege” (no punishment without law) and is theoretically governed solely by national laws. Civil and administrative law areas are even more intricate.

Professor Luo specifically mentioned Article 44 of the Education Law, which stipulates that students (including those in schools, vocational training, continuing education, or even employees in corporate training programs) must fulfill their obligation to “study hard and complete assigned learning tasks.” However, how “studying hard” is evaluated can range broadly—from achieving perfect scores and staying focused in class to merely attending classes and avoiding failing grades—meaning almost everyone could be considered in violation of the law. Although no penalties are specified for such “violations,” it doesn’t mean they aren’t unlawful.

In my work, I’ve encountered similar issues. For example, in cases involving widespread violations within a group, should every individual be treated as a criminal under the Criminal Code? After all, as ordinary people, many are unaware that their actions constitute crimes. Even I, without thorough research and confirmation, couldn’t always judge beforehand whether such actions were criminal based on experience or intuition. It’s only during investigations, through compiling various laws, regulations, and administrative rules, that I realize, “Oh, so this can be a crime too.”

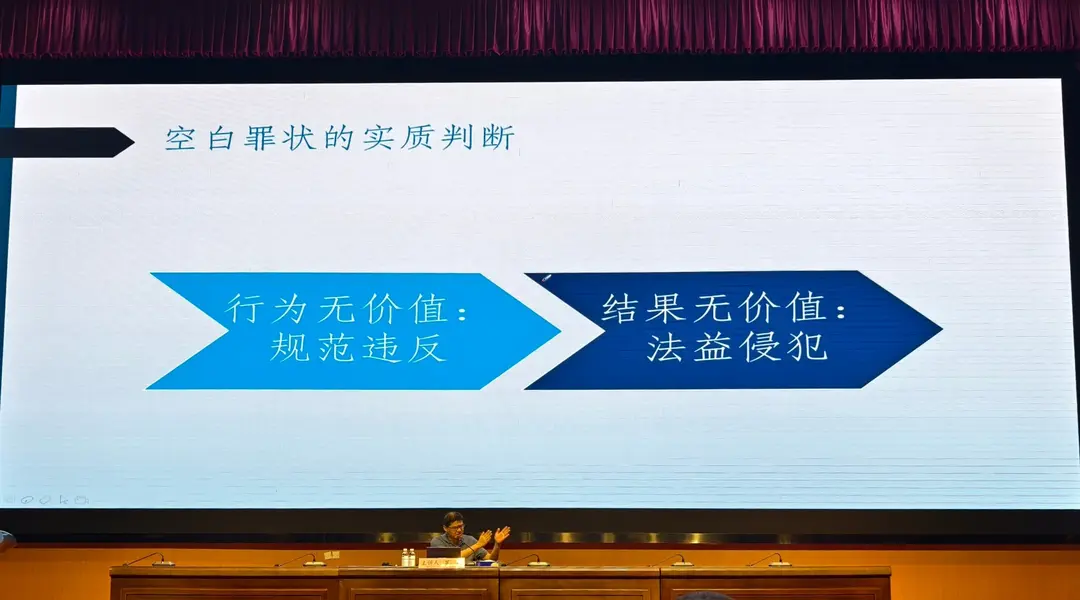

After the lecture, I overheard someone chatting on their way out, questioning Professor Luo’s statement that “both act wrongfulness and result wrongfulness must be satisfied to constitute a crime,” arguing that it conflicts with current criminal justice practices and wondering why the organizers didn’t intervene.

I was taken aback for a moment, recalling that such a point had been made during the lecture. But upon reviewing the photos of the slides I took, I realized Professor Luo was discussing the substantive judgment of “blank criminal provisions.” For situations where the Criminal Code doesn’t directly define the elements of a crime, requiring both conditions isn’t necessarily “absurd.” At least in the cases he cited, it made sense. However, in judicial practice, some offenses described through “blank provisions” (like dangerous driving) don’t always strictly follow the model of “simultaneous in-depth evaluation of act wrongfulness and result wrongfulness” as analyzed in his examples, especially when the regulations clearly define the constitutive acts.

This post-lecture episode made me shudder. A nearly “literal interpretation” could have cast an “invisible shadow” over the event if someone had made a big deal out of it. Fortunately, the lecture was held at a university—perhaps the organizers had considered the venue carefully—allowing this high-quality session to proceed smoothly and conclude successfully.

Master Teachers Have Always Been Around

Ever since I learned that Professor Luo Xiang would be lecturing at Foshan University, I’ve been pondering: What if I had studied harder in high school, scored 40 more points, and entered China University of Political Science and Law? How would being taught by a “master teacher” like him have shaped my outcomes?

Seeing Professor Luo in person, with his height seemingly half a head taller than the average Hunanese, even made me doubt if he was truly from Hunan. This stark contrast immediately reminded me of my university criminal law teacher, Professor Peng, who was quite petite, typical of our “Jianghu laobiao” (fellow provincials).

I still remember Professor Peng as a “young man” when he taught us criminal law—amiable and humble, yet his slightly tinted glasses gave him an enigmatic air. His smiling questions always seemed to hide traps. But it was precisely because he avoided dry textbook recitations, instead sharing his own learning and life experiences, discussing typical social cases, asking about our ideals and futures, and critiquing flaws in criminal justice practice, that he felt like an elder brother chatting with us. This added a light-hearted touch to the serious study of criminal law.

His personal story, shared in class, has stayed with me and often comes to mind when I meet people with similar backgrounds in my work.

In short, Professor Peng was born into a poor rural family in Jiangxi. Despite his diligence and excellent grades, family pressures led him to choose a “normal school” path—a quick route to changing his fate in the countryside, securing a coveted “iron rice bowl” as a rural teacher after graduation. However, teaching in a village school reinforced his belief that “education changes destiny.” While working, he earned a college diploma and later passed the entrance exam for Zhengzhou University’s graduate program, eventually “leaping over the dragon gate” to become a university professor.

Professor Peng taught criminal law at Foshan University’s Law School (formerly the School of Politics and Law) for 11 years. The year we graduated, he left Foshan for Soochow University’s Wang Jian Law School. As he moved away from Guangdong and we entered society, we lost touch with him.

Seizing the moment, I searched online for updates on Professor Peng and was instantly overwhelmed with emotions.

In June this year, Professor Peng transferred to China University of Political Science and Law, where he now serves as a professor, doctoral supervisor, and Dean of the Institute of Evidence Law and Forensic Science. To my surprise, this institute hosts a Key Laboratory of the Ministry of Education—a rarity in humanities and social sciences universities—chaired by an academician of the Chinese Academy of Engineering, somewhat breaking the stereotype that “liberal arts universities have no academicians.”

When I shared this news in our university class group chat, our homeroom teacher immediately responded: “Professor Peng is one of the few prolific jurists in our country.”

So, “master teachers” have always been right in front of us. We, too, were students taught by such “master teachers” like Professor Luo Xiang. Reflecting on my earlier thoughts, I couldn’t help but sigh at my own foolishness.

Personal Efforts Must Consider Historical Context

I had planned to write this article right after Professor Luo’s lecture the day before yesterday. But since there was another lecture today by Professor Huang Jin, former president of China University of Political Science and Law, I decided to include it here.

Unlike Professor Luo’s internet fame, Professor Huang is highly esteemed within legal academia and higher education circles. He was the first doctoral graduate in private international law trained in New China, an inaugural “National Outstanding Young Jurist,” and has made significant contributions to China’s foreign-related rule of law development.

Although both events involved bar associations, Professor Huang’s lecture was held in a government auditorium, differing in setting from Professor Luo’s. Stylistically, they also varied.

Professor Huang’s lecture focused more on theoretical exposition, systematically covering the concept and内涵 of foreign-related rule of law, reviewing the history of China’s foreign-related rule of law development, and discussing ways to advance its construction.

I’ve attended similar lectures multiple times before, especially during training at Northwest University of Political Science and Law, where I was first introduced to the concept of foreign-related rule of law. It left a deep impression, particularly when the instructor presented data highlighting the challenges facing China’s foreign-related rule of law efforts, which left everyone feeling uneasy.

Among nearly 700,000 lawyers in China, fewer than 10,000 can handle foreign-related legal practice, less than 300 can participate in overseas litigation or arbitration hearings, and fewer than 30 can provide international legal services in dispute resolution bodies like the WTO. In terms of constructing foreign-related rule of law systems, over 95% of import-export contracts choose foreign law, China’s loss rate in overseas courts or arbitration exceeds 95%, and over 95% of cases handled by domestic foreign-related institutions involve Mainland China plus Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan. In UN agencies, Chinese staff comprise less than 1/15 of China’s contribution share, with almost none in legal roles, leaving China with little voice in international legal rule-making. (2022)

Overall, foreign-related rule of law remains a weak spot for China, both now and for the foreseeable future. Professor Huang’s lecture essentially called for greater attention, support, and participation in building this field.

Much like the burgeoning legal system during the early reform and opening-up era, pioneers like Professor Huang ventured into uncharted territories like private international law, laying a solid foundation for future generations. Today, as China’s opening-up broadens and deepens, numerous new “uncharted territories” in foreign-related rule of law await exploration by domestic legal professionals. In my spare time, I’ve always kept an eye on these issues, having written a few basic普法 articles—perhaps as a way to combat the ever-present anxiety of being a “legal illiterate.”

#university #criminal law #foreign-related rule of law